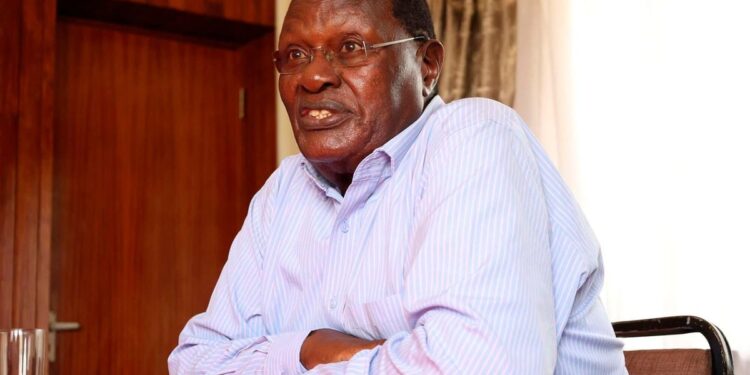

It was the eve of budget reading on Thursday, June 13, 2002, and Finance minister Chris Obure had not completed his speech.

He wasn’t even sure that the budget presentation would proceed the following day in Parliament. As darkness enveloped the city, the desperation was palpable inside his Treasury Building office on Harambee Avenue.

The math was not adding up. Mr Obure was anxiously waiting for aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He waited. And waited. At some point, the mandarins in then-President Moi’s besieged Kanu government contemplated the worst.

“We had agreed generally that we would withdraw our budget because we could not meet all our requirements,” Mr Obure recalled the dramatic events in an interview with the Nation recently. The international community, he said, had promised to reopen the aid taps after a crippling freeze. Treasury officials were eagerly awaiting this assistance to factor it in the 2002/2003 financial year.

Kenya’s economy was in shambles and a severe drought had aggravated the situation. But the donors failed to come through in the clutch.

Catch-22 situation

“So, it’s a day to budget reading and you have not written your speech. I didn’t enjoy my work at that time. It was very difficult. Those are some of the things that sometimes people go through if you are put in that kind of position,” the former minister said. He explained that Moi, who was retiring that year after 24 years in power, had found himself in a catch-22 situation.

“What could he do? If you are running a strong economy, you can say to hell with them, isn’t it?” Mr Obure posed. “But you are not in a position to do so because you need their help to save the country and your administration.”

Two decades later, the IMF is back as a key lender to Kenya along with its strict conditions including prescribing more taxes and restructuring of State agencies. Anti-Finance Bill protesters have accused the IMF of pushing the government to implement policies that hurt citizens.

Last week, as anti-tax protests turned bloody, the IMF was forced to defend itself, insisting that its intervention was aimed at helping Kenya “overcome the difficult economic challenges it faces.” Ms Julie Kozack, IMF Director of Communications, regretted the killings as police battled protesters.

“We are deeply concerned about the tragic events in Kenya in recent days and saddened by the loss of lives and the many injuries. Our thoughts are with all the people affected by the turmoil in the country,” the official said. “The IMF is closely monitoring the situation in Kenya. Our main goal in supporting Kenya is to help it overcome the difficult economic challenges it faces and improve its economic prospects and the well-being of its people.”

“We are committed to working together with Kenya to chart a course towards robust, sustainable, and inclusive growth,” Ms Kozack added.

Brave face

For Obure, he wouldn’t want Kenya to be at the mercy of the IMF ever again.

“Looking back, I don’t even know how we survived,” he says.

But the Finance minister put up a brave face while reading the budget speech, assuring Kenyans that the ship was steady, confident that the behind-the-scenes frustrations and the fact that the country was barely getting by was a well-kept secret.

“We are encouraged that our economy, our people and our government were sufficiently resilient to withstand those very severe and adverse economic events and external shocks,” Mr Obure told Parliament, citing severe drought and rampant poverty among other challenges.

“We sustained the economy through the admirable determination of the hard-working Kenyans who courageously weathered the hardships and redoubled their efforts to produce bumper agricultural harvests and other goods and services.”

In his 36-page speech, the minister only hinted at the standoff with the IMF in two paragraphs. “We were further affected by the continued withholding of budget support by the IMF, the World Bank and the main donor countries,” Mr Obure told MPs.

“Our economy was negatively affected by the strained relations with the IMF and other development partners who suspended disbursement of committed budget support funds in 1997 and again in November 2000. Despite intensified dialogue and strengthening of our governance and anti-corruption efforts, the IMF has not lifted the suspension of disbursements,” he added.

With Kenya on the brink of an economic meltdown against the backdrop of widespread financial difficulties, runaway corruption and inflation, President Moi had reshuffled his Cabinet in November 2001 hoping to placate donors. The President had moved Mr Obure to Treasury after his short stint at the Foreign Affairs ministry.

Terrorism issues

Mr Obure, who was one of the longest-serving members of the Moi administration having first been appointed assistant minister for Labour in 1984 with Robert Ouko as his minister, told the Nation that he quickly noticed the indifferent reception he got as finance minister compared to his stint at foreign affairs.

“I remember when I went to the US, for example, as Foreign Affairs minister (I was warmly received) because they needed us more at the time to deal with the terrorism issues after the attack on September 11, 2001. When I went to the finance docket, the treatment was very different,” Mr Obure recalled.

At Foreign Affairs, he explained, “they would even invite me as a special guest.” “A few months later, I am minister for Finance, I need them most and they are nowhere near to listen to us. We were in a very difficult situation,” he reminisces.

Mr Obure’s transfer to the Finance docket was seen as an attempt by President Moi to get a more diplomatic minister to front negotiations with the IMF and the World Bank.

The Bretton Woods institutions had fallen out with Mr Obure’s predecessor, Mr Chris Okemo.

They had also lost patience with the Moi regime because of deepening economic problems even after the President appointed a ‘Dream Team’ comprising high-level technocrats to turn round the economy in 1999. Mr Obure said some members of the Dream Team attempted to create two centres of power in the Moi administration since they wielded immense powers courtesy of the international community.

“Some of these people operated as if they were not under Moi. Some even disrupted operations in some ministries, and I remember one of them cautioning my staff when I served in the Agriculture docket against giving me information,” he says.

President Moi’s economic recovery team consisted of renowned conservationist and former Kenya Wildlife Service director Richard Leakey as Secretary to the Cabinet and Head of Civil Service, Martin Oduor-Otieno as the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance and Planning and Mr Mwangazi Mwachofi, the resident representative of the South Africa based International Finance Corporation as the Financial Secretary.

Others were former Kenya Airways Managing Director Titus Naikuni as the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Transport and Communications, Dr Shem Migot Adholla a lead specialist for rural development in Africa at the World Bank as the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture and Mr Wilfred Mwangi from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre as the Energy Permanent Secretary.

The IMF had discontinued aid to Kenya in 2000 because of the country’s failure to fulfil promises made on tackling corruption and privatising the economy.

“We believe the reform process is important for Kenya, and a fundamental pillar of that is governance,” Mr Samuel Itam, the IMF’s senior resident representative in Nairobi said at the time.

Mr Obure said the bones of contention were the need for a constitutional amendment to re-establish the Kenya Anti-Corruption Authority (KACA) within a legal framework, legislation dealing with corruption and economic crimes, and code of conduct for all three arms of government – the executive, legislature and judiciary.

Mr Callisto Madavo, the World Bank’s Washington-based regional vice-president at the time, had informed the country of the bank’s decision to suspend its remaining credit line of Sh2.4 billion for the emergency rehabilitation of roads, over alleged corruption cases.

“We had to rely on local resources, which were very inadequate. Now you imagine a situation where you are not raising adequate resources locally and you cannot expect support from the international community,” Mr Obure said. He recalled that President Moi was treading on very shaky ground amid rising opposition ahead of his retirement in 2002, and the tension in government was palpable.

“That’s why we were doing all these reforms in the various sectors in order to put ourselves in a position where we would be seen to be managing our resources better,” the ex-minister said.

Demanded more

Mr Obure recounted that, even when the Moi administration thought it had done the best it could, the international community and the donors demanded more.

“They said, ‘do it this way, or we don’t give you support,’” he said.

“They said, ‘in order for us to deal with you, to accommodate the requests you are making, we want you to carry out the following reforms,” he said, adding that one of the measures included setting up a national audit office.

“Then they said they want us to enact a new law to govern procurement. So, you go the whole way and do the Exchequer and Audit (Public Procurement) Regulations, 2001 and you report to them only for them to demand that we stop the famous (Joe) Donde Bill which sought to cap bank interest rates,” he went on.

Mr Donde, the Gem MP at the time, wanted to put a ceiling on interest rates charged on loans and advances given to borrowers because lenders were charging exorbitant levies in excess of the principal amount.

“People were losing their properties because they couldn’t afford to repay. Now they come round and say, ‘stop that Bill.’ How do you stop it? So, we were arguing with them and saying, look, this is a hugely popular Bill and Parliament is equally an independent institution that executive cannot interfere with, what do we do?”

Mr Obure underscores the need to build the country’s economy to remain afloat as a nation and cut reliance on international lenders.

“A strong economy is important. If you can manage your own local resources, you become independent and more respectable,” Mr Obure says.

President Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki, presided over an economic boon that saw the country cut its dependence on foreign aid.

But President Kibaki’s successor, Uhuru Kenyatta, piled up more foreign debt that has grown even bigger under President William Ruto’s administration.

“From experience, I don’t want us to be in the situation where we were at that time.,” Mr Obure said. “It was not pleasant at all.”